Understanding Aperture in Photography

Aperture (also known as F-Stop) is probably the most important camera setting in photography!

Aperture is one of the three pillars of photography (the other two being Shutter Speed and ISO, which are two other chapters in our Photography Basics guide). Of the three, aperture is certainly the most important. In this article, we go through everything you need to know about aperture and how it works.

What is Aperture?

Aperture can be defined as the opening in a lens through which light passes to enter the camera. It is an easy concept to understand if you just think about how your eyes work. As you move between bright and dark environments, the iris in your eyes either expands or shrinks, controlling the size of your pupil.

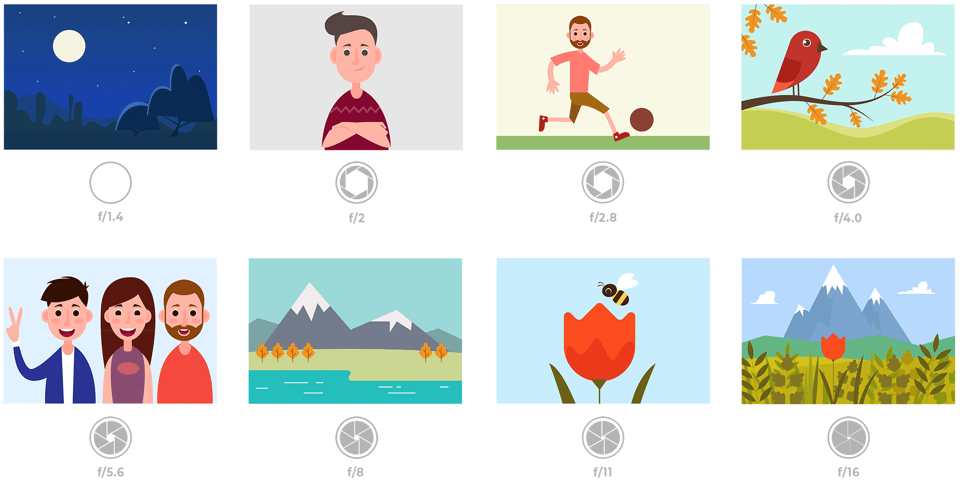

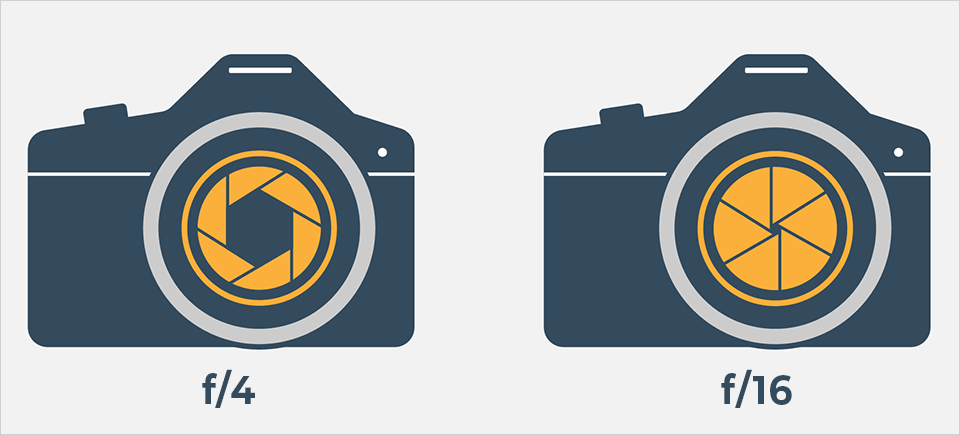

In photography, the “pupil” of your lens is called aperture. You can shrink or enlarge the size of the aperture to allow more or less light to reach your camera sensor. The image below shows an aperture in a lens:

Aperture can add dimension to your photos by controlling depth of field. At one extreme, aperture gives you a blurred background with a beautiful shallow focus effect. This is very popular for portrait photography.

At the other extreme, it will give you sharp photos from the nearby foreground to the distant horizon. Landscape photographers use this effect a lot.

On top of that, the aperture you choose also alters the exposure of your images by making them brighter or darker.

How Aperture Affects Exposure

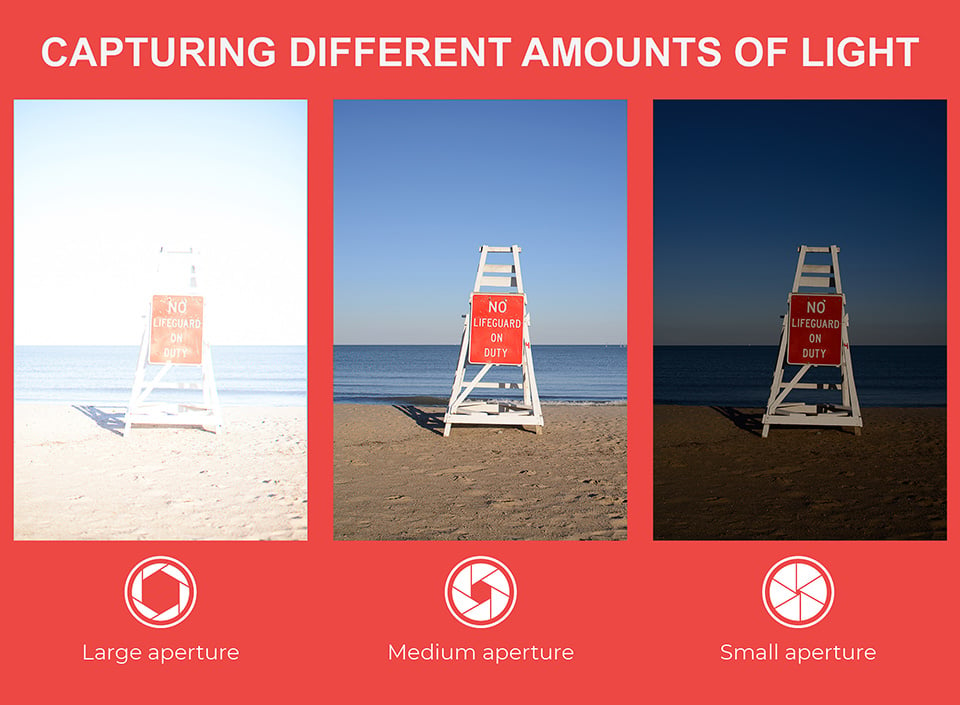

Aperture has several effects on your photographs. Perhaps the most obvious is the brightness, or exposure, of your images. As aperture changes in size, it alters the overall amount of light that reaches your camera sensor – and therefore the brightness of your image.

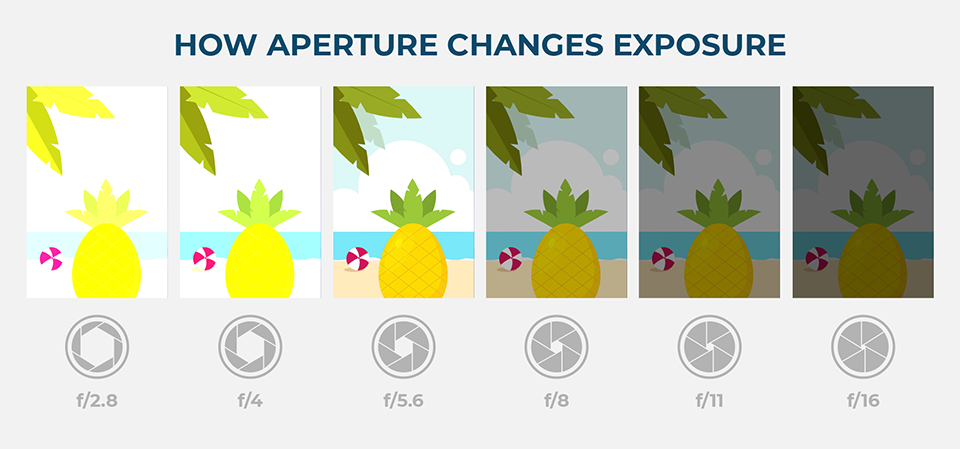

A large aperture (a wide opening) will pass a lot of light, resulting in a brighter photograph. A small aperture does just the opposite, making a photo darker. Take a look at the illustration below to see how it affects exposure:

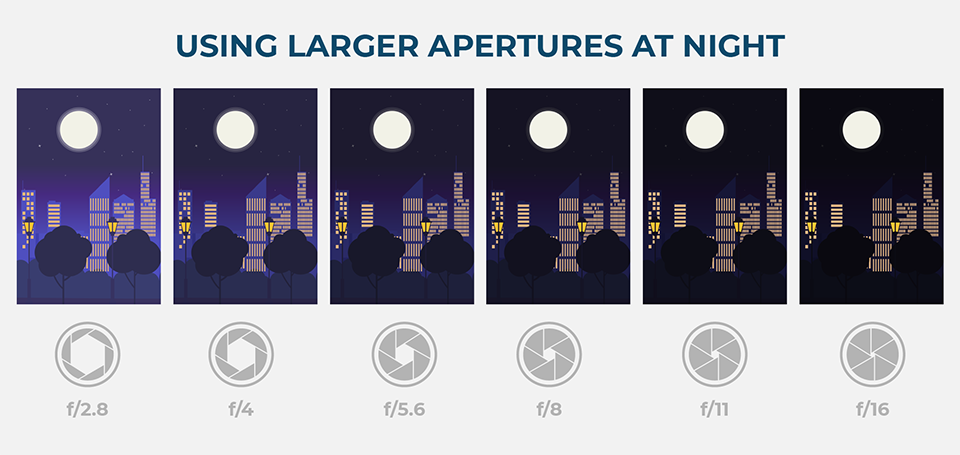

In a dark environment – such as indoors or at night – you will probably want to select a large aperture to capture as much light as possible. This is the same reason why people’s pupils dilate when it starts to get dark; pupils are the aperture of our eyes.

How Aperture Affects Depth of Field

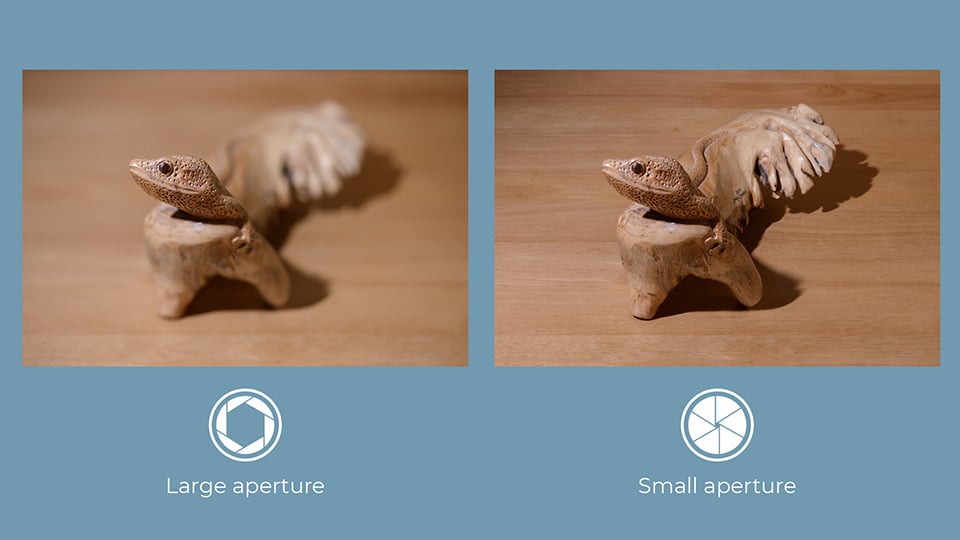

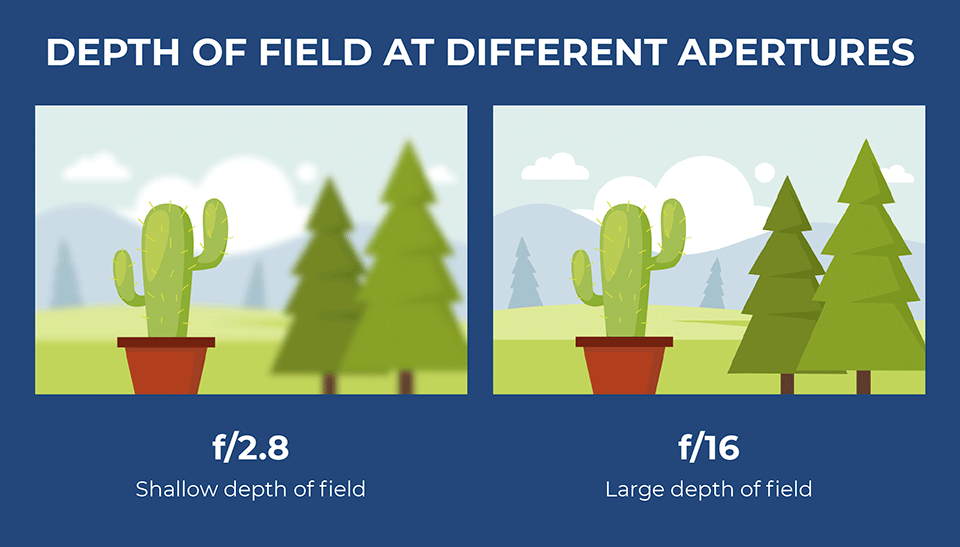

The other critical effect of aperture is depth of field. Depth of field is the amount of your photograph that appears sharp from front to back. Some images have a “thin” or “shallow” depth of field, where the background is completely out of focus. Other images have a “large” or “high” depth of field, where both the foreground and background are sharp.

For example, here is an image with a shallow depth of field:

In the image above, you can see that the girl is in focus and appears sharp, while the background is completely out of focus. My choice of aperture played a big role here. I specifically used a large aperture in order to create a shallow focus effect (yes, the larger your aperture, the bigger this effect). This helped me bring the attention of the viewer to the subject, rather than busy background. Had I used a narrower aperture, the subject would not be separated from the background as effectively.

One trick to remember this relationship: a large aperture results in a large amount of both foreground and background blur. This is often desirable for portraits, or general photos of objects where you want to isolate the subject. Sometimes you can frame your subject with foreground objects, which will also look blurred relative to the subject, as shown in the example below:

Quick Note: The appearance of the out-of-focus areas (AKA whether it looks good or not) is often referred to as “bokeh“. Bokeh is the property of the lens, and some lenses have better bokeh than others. This article explains how to get better bokeh as a photographer. Even though some lenses are better than others, almost all lenses are capable of a nice shallow focus effect if you use a large aperture and get close enough to your subject.

On the other hand, a small aperture results in a small amount of background blur, which is typically ideal for some types of photography such as landscape and architecture. In the landscape photo below, I used a small aperture to ensure that both my foreground and background were as sharp as possible from front to back:

Here is a quick comparison that shows the difference between using a large vs a small aperture and what it does to your depth of field:

As you can see, in the photograph on the left, only the head of the lizard appears in focus and sharp, while the background and foreground are both transitioning into blur. Meanwhile, the photo on the right has everything from front to back appearing in focus. This is what using large vs small aperture does to photographs.

What Are F-Stop and F-Number?

So far, we have only discussed aperture in general terms like large and small. However, it can also be expressed as a number known as “f-number” or “f-stop”, with the letter “f” appearing before the number, such as f/8.

Most likely, you have noticed aperture written this way on your camera before. On your LCD screen or viewfinder, your aperture will usually look something like this: f/2, f/3.5, f/8, and so on. Some cameras omit the slash and write f-stops like this: f2, f3.5, f8, and so on. For example, the Nikon camera below is set to an aperture of f/8:

So, f-stops are a way of describing the size of the aperture for a particular photo. If you want to find out more about this subject, we have a comprehensive article on f-stop that explains why it’s written that way and is worth checking out.

Large vs Small Aperture

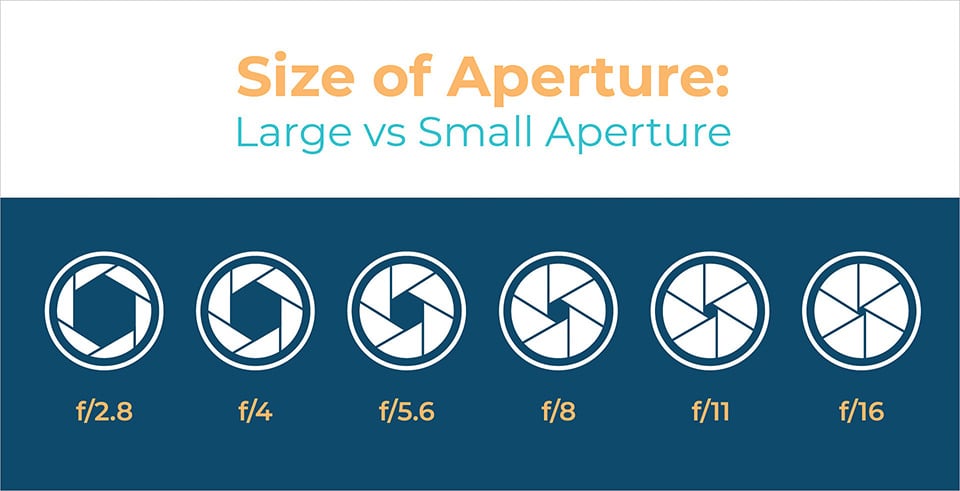

There’s a catch – one important part of aperture that confuses beginning photographers more than anything else. This is something you really need to pay attention to and get correct: Small numbers represent large apertures, and large numbers represent small apertures!

That’s not a typo. For example, f/2.8 is larger than f/4 and much larger than f/11. Most people find this awkward, since it goes against our basic intuition. Nevertheless, this is a fact of photography. Take a look at this chart:

This causes a huge amount of confusion among photographers, because it’s completely the reverse of what you would expect at first. However, there is a reasonable and simple explanation that should make it much clearer to you: Aperture is a fraction.

When you are dealing with an f-stop of f/16, for example, you can think of it like the fraction 1/16th. Hopefully, you already know that a fraction like 1/16 is clearly much smaller than the fraction 1/4. For this exact reason, an aperture of f/16 is smaller than f/4. Looking at the front of your camera lens, this is what you’d see:

So, if photographers recommend a large aperture for a particular type of photography, they’re telling you to use something like f/1.4, f/2, or f/2.8. And if they suggest a small aperture for one of your photos, they’re recommending that you use something like f/8, f/11, or f/16.

How to Pick the Right Aperture

Now that you’re familiar with large vs small apertures, how do you know what aperture to use for your photos? Let’s revisit two of the most important effects of aperture: exposure and depth of field. First, here is a quick diagram to refresh your memory on how aperture affects the exposure of an image:

If you’ve read the prior chapter in our Photography Basics guide covering shutter speed, you already know that aperture isn’t the only way to change how bright a photo is. Nevertheless, it plays an important role. In the graphic above, if I didn’t allow myself to change any other camera settings like shutter speed or ISO, the optimal aperture would be f/5.6.

In a darker environment, where you aren’t capturing enough light, the optimal aperture would change. For example, you may want to use a large aperture like f/2.8 at night, just like how our eye’s pupils dilate to capture every last bit of light:

As for depth of field, recall that a large aperture value like f/2.8 will result in a large amount of background blur (ideal for shallow focus portraits), while values like f/8, f/11, or f/16 will give you a lot more depth of field (ideal for landscapes and architectural photography).

In fact, depth of field is the part of aperture that I recommend thinking about the most. My process for almost every photo I take goes like this:

- Ask myself how much depth of field I want

- Set an aperture that achieves it

- Set a shutter speed that makes my photo the proper brightness

- If that shutter speed leads to unsharp photos thanks to too much motion blur, dial back the shutter speed and raise my ISO instead

- Win photo contest 🙂